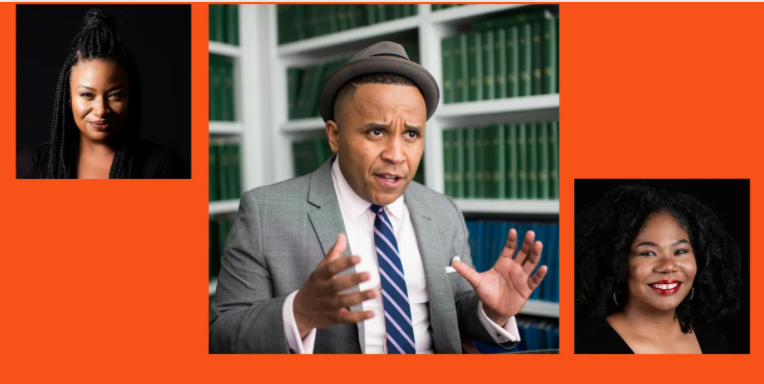

Arisha Hatch, Rashad Robinson and Brandi Collins-Dexter of Color of Change have been leading a fight to help Big Tech grapple with civil rights issues. | Image: Color of Change and Protocol

It felt hot in Brandi Collins-Dexter’s attic, but nerves may have had something to do with it.

It was late June, and she was sitting in front of her computer, her back against a brick wall, the breakfast she hadn’t had time to eat sitting just out of frame. She’d carefully selected a pair of cross earrings to wear for the occasion, channeling her Catholic upbringing and hoping they’d go over well with the members of Congress who would be peppering her with questions all morning as part of a virtual hearing on disinformation campaigns and social media.

The truth is, Collins-Dexter, who once aspired to be a constitutional lawyer, hates testifying before Congress. But she’s done it twice in the last year and a half, because as lawmakers have become increasingly interested in regulating tech giants, they’ve wanted to hear from the people who have been instrumental in spotting — and calling out — Big Tech’s flaws.

Collins-Dexter is one. At Color of Change, the civil rights nonprofit where she has spent the last six years, she has helped engineer some of the organization’s most impactful campaigns, designed to help stop racist content from spreading online and hold tech companies accountable for the myriad ways they fail Black and brown people.

The hearing would be one of her last big acts as senior campaign director, before stepping back from her full-time role at the organization to write a book, and the timing of her testimony couldn’t have been more apt. The week before, Color of Change and a slew of other advocacy organizations, including the Anti-Defamation League and the NAACP, began urging Facebook advertisers to boycott the platform for the month of July as part of a campaign called #StopHateforProfit. In a little over a week, brands as large as Verizon and Unilever had signed on.

When her name was finally called that morning in the attic, Collins-Dexter was nervous, but she also had power on her side. She launched into a speech about the “hundreds and hundreds” of complaints Color of Change has received from people who say they’ve been censored, harassed and violently threatened on Facebook. She argued that dangerous misinformation about coronavirus on social media was partly to blame for COVID-19’s body count. Before her five minutes were up, she ended with a plea: “Members of Congress, please move quickly to fix our democracy before it’s irretrievably broken.”

Color of Change’s founders didn’t set out to take on Facebook or the broader tech industry; they launched the organization in the post-Hurricane Katrina days of 2005, focused on getting people shelter, care and justice under the law, and convincing the government to, as Kanye West put it at the time, “care about Black people.” But over the last few years, tech’s impact on bread-and-butter civil rights issues like housing and voting has become impossible to ignore. And so, since around 2013, Color of Change, a civil rights group born of and for the social media generation, has turned its attention to tech companies, rallying its members to sign petitions and join campaigns that pressure Facebook, Airbnb and others to change their ways.

Back in 2014, it helped lead the charge to get Twitter to publish its internal diversity statistics for the first time. That same year, it campaigned to get GoFundMe to take down a fundraising page for Darren Wilson, the Ferguson cop who killed Michael Brown. And, more recently, it successfully pushed Zoom to create a chief diversity officer position, following a flood of racist Zoombombings in the early days of the pandemic.

Brandi Collins-Dexter testified before Congress in June as part of a virtual hearing on disinformation campaigns and social media.Image: C-Span and ProtocolColor of Change is certainly not the most storied civil rights organization in the country. The NAACP, it is not. And it’s not alone among advocacy organizations taking tech to task. But Color of Change stands apart for its digital fluency and the speed with which its leaders have staked out a seat at the very tables — including Mark Zuckerberg’s dinner table — where the world’s most powerful business leaders are making decisions that could help or hurt billions of people around the world.

“Over the last five or six years, I think Color of Change has moved from sitting on the edge of that table to, ‘This can’t [happen] without working with and collaborating with Color of Change,'” said Craig Aaron, co-CEO of Free Press, a group that pushes for media reform and has partnered with Color of Change on campaigns including #StopHateForProfit. “They are a group that’s willing to work a bunch of angles and try a bunch of tactics inside and outside, but even when they’re on the inside, they bring it. They don’t back down, and they don’t deliver a different message.”

Color of Change has partnered with some of the country’s oldest civil rights groups, rallying public support to complement the policy work that organizations like the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund focus on. “Our forces combine to be powerful in these conversations,” said Vanita Gupta, president and CEO of the Leadership Conference, who previously led the civil rights division at the Department of Justice. “We’re bringing different sets of relationships, different areas of expertise, and [Color of Change] is bringing the grassroots power.”

Color of Change’s outspokenness and visibility have come with their own risk. Its leaders have often been subject to the same online harassment they seek to stop, forcing them to hire a security team and move offices for their own safety. And the organization’s status as a media darling has led some of its collaborators and targets alike to quibble privately about who should really be getting the credit.

But Color of Change has only gotten stronger: Since May, its membership has exploded from 1.7 million to 8 million people, buoyed by the country’s biggest civil rights movement since the 1960s. Now, as CEOs across the country vow to do more to address racial injustice, Color of Change is in a prime position to hold them to it.

“We’ve made ourselves unignorable,” Color of Change’s media-savvy president, Rashad Robinson, said. “Being unignorable means they’re going to have to navigate you.”

Born to win

Color of Change isn’t a Silicon Valley tech startup, but its origin story reads like one. Before he became a civil rights advocate, founder James Rucker graduated from Stanford University, where he majored in symbolic systems, an interdisciplinary study combining computer science, linguistics, philosophy and cognitive psychology. After that, he launched and led a failed AI company before joining MoveOn, the progressive advocacy group whose main medium was email, in 2003 as the director of grassroots mobilization.

Two years later, Katrina hit, and while Rucker was proud of the work he was doing at MoveOn, he wanted to focus on speaking primarily to and for Black people, who were most devastated by the disaster. “No one gets in trouble, no politician loses by turning their back on or not servicing the needs of Black folks,” Rucker said.

He recruited his friend Van Jones to be the co-founder of a new organization that he hoped could apply the MoveOn model to civil rights issues. Rucker built the first version of the website himself, and in late 2005, he pushed send on Color of Change’s first email blast, which went out to around 1,200 people. The subject line: “Kanye was right.”

Color of Change blew up, amassing 10,000 members in a matter of weeks. Working out of the Bay Area, Rucker focused his energy on issues such as housing, police violence against survivors, and FEMA’s many failures. Soon, the group broadened its focus beyond Katrina. In 2007, it organized a protest and funded the legal defense team for a group of Black students, known as the Jena Six, who were facing decades in prison for a schoolyard fight that came in the wake of a series of racist incidents.

Years passed, and while Rucker’s idea had taken off, he said he always planned to hire someone else to run Color of Change long term. It just took about five years longer than he expected. “We needed to find someone who understood the political landscape, organizing, was a good writer, knew how to hold folks accountable, and [didn’t mind] the discomfort that comes if you do the work well,” Rucker said. “The skills you need are skills you get paid a lot of money for in the for-profit world.”

People want to be part of something that wins.

Then he met Robinson, who was then the senior director of media programs at GLAAD, working on changing public perception regarding LGBTQ+ people, in part, by embracing digital media. Robinson had been an organizer and activist since his high school years, when he convinced a slew of New York City TV stations to cover a protest he’d planned against the Rite Aid near his high school, which was banning students, accusing them of shoplifting. (“We had signs that said, ‘Rite Aid ain’t right,'” Robinson said).

“He’s a pretty unafraid kind of guy,” Rucker said. “I was excited about all the experiences he brought — and his brain.”

Though it was still relatively small, with a full-time staff of five and an email list of around 600,000 people, Color of Change scored some big wins. Shortly after Robinson joined, Fox canceled conservative commentator Glenn Beck’s show, following a two-year campaign during which Color of Change pressured advertisers to boycott Beck for calling President Obama a racist on-air.

Robinson remembered sitting in Color of Change’s Bay Area office, watching the final episode with the team and taking note of the last remaining advertisers on Beck’s show. “It was that company where you put gold in an envelope, and they send back cash,” Robinson said triumphantly. “It felt like an absolute win.”

Later, Color of Change successfully urged major corporations like Pepsi and Coca-Cola to break ties with the American Legislative Exchange Council, the right-wing group better known as ALEC that had pushed voter ID laws as well as stand-your-ground gun laws in states across the country.

Along the way, the organization meticulously catalogued its triumphs in email blasts and press releases, eagerly taking victory laps each time one of its targets decided to do the right thing. To Robinson, “winning” was and remains key to growing the organization. “People want to be part of something that wins,” he said.

Next stop: Silicon Valley

A few years into Robinson’s tenure, a conversation started brewing in certain corners of Silicon Valley about the lack of diversity in tech, and it got him thinking. “When a company has diversity problems, they have other problems,” he said. “An industry has other problems.”

Color of Change hired a consultant to survey the tech landscape for evidence of those problems. By then, a lawyer-turned-community organizer named Arisha Hatch had joined the organization. (She now serves as its chief of campaigns.) Together with the consultant, Hatch held a round of interviews with tech workers at every level of seniority at companies including Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Pandora, Dropbox, Apple and Google.

“What we came to was, although they were probably well-intentioned, there were a lot of ways in which tech companies were undoing or unraveling decades and decades of Black-led activism around voting rights, housing discrimination, surveillance — a whole set of hard-fought wins,” Hatch said. Case in point: Around the same time, the hashtag #AirbnbWhileBlack had begun trending, driven by Black people telling stories of being shut out of Airbnb bookings due to their race. To the Color of Change team, this was a digital form of redlining, part of an ugly tradition of housing discrimination that civil rights activists before them had fought to stop.

Color of Change’s leaders set about fundraising for a new effort aimed at tech companies and hired Collins-Dexter, who previously worked at the Center for Media Justice, to head it up. Airbnb was one of its early targets.

There were a lot of ways in which tech companies were undoing or unraveling decades and decades of Black-led activism.

Initially, Collins-Dexter said the company was hesitant about meeting with the team, but once the hashtag took off, she said, “Airbnb got back to us right away. They were really hyperconscious of their brand.”

In 2016, Collins-Dexter, Hatch and Robinson visited Airbnb’s headquarters in San Francisco. Over the prior year, they’d been to a lot of these types of meetings at other companies, with junior-level staffers and, Collins-Dexter said, “whatever one Black person works somewhere.”

But when they got to Airbnb, the company’s co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky joined them.

He listened as Robinson told stories about his grandfather, who’d grown up in the South during the Green Book era, and who, even decades later, would hesitate to make a pit stop on long car rides. The story resonated with Chesky, indicating, he told Protocol, that Robinson was on the “frontline of this battle.”

“Rashad described his grandfather’s experience feeling unwelcome while traveling. No one should be made to feel that way, and I certainly don’t want anyone on our platform to feel or be treated that way,” Chesky said.

Robinson swears he wasn’t trying to garner sympathy with Chesky, and instead viewed the story as a warning shot. “I want to both appeal to their sense of what’s right and help them understand things that their education, their life experience hasn’t provided,” he said. “But I also want to really be clear and let them know: If they don’t do the right thing, this is how I’m going to deal with them publicly.”

Chesky asked the team to give him two weeks to deliver a plan before launching a campaign against Airbnb. “Something that stuck with me was he said, ‘We’re willing to leave money on the table to get this right,'” Collins-Dexter remembered. “I don’t ever hear CEOs say that.”

Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky was moved by the story that Rashad Robinson told him on their first meeting.Photo: Mike Cohen/Getty Images for The New York TimesA few weeks later, Chesky told them Airbnb would be launching a full internal civil rights audit, which was still a novel concept at the time. (An Airbnb spokesperson said the company had been considering an audit since before its meeting with Color of Change). The effort, Airbnb decided, would be led by Laura Murphy, a civil rights leader who formerly led the American Civil Liberties Union’s legislative office.

That pick impressed Collins-Dexter. “She had the credentials we valued,” she said. “She brought a different lens of seriousness to the work.”

Murphy, meanwhile, had been an admirer of Color of Change’s work as well. “They’re brilliant strategists,” Murphy said. “They’re playing a very impactful and critical role because of their mastery of online advocacy.”

Murphy delivered the results of the audit that September, and with it came a sweeping array of commitments from Airbnb, designed to mitigate the issues she’d uncovered. Airbnb announced it would create a new anti-discrimination team, stacked with engineers and data scientists whose main job was to root out the possibility for bias on the platform. One major change that came from that work: Removing photos from people’s accounts pre-booking. Airbnb also began requiring all users to agree to a nondiscrimination policy, which it says cost it business: Since 2016, 1.3 million users have been removed from the platform for refusing to agree to those terms.

Margaret Richardson, Airbnb’s vice president of trust, was reluctant to exclusively attribute all of that work to Color of Change’s advocacy, naming the Leadership Conference as a key partner. But she said Color of Change does fill a singular role in the civil rights landscape.

“They are uniquely focused on and familiar with the challenges of discrimination online,” Richardson said. “Their membership has a lot of the age demographics that Airbnb appeals to as well: a younger, more digital native group of users who are thinking of these issues in ways that are evolving constantly.”

Even four years later, Collins-Dexter said Airbnb’s response is still “the most robust plan I’ve ever seen a corporation lay out.” And when the company was forced to make layoffs due to COVID-19, she was impressed to see that Airbnb didn’t cut its anti-discrimination team. Instead, it dedicated even more resources to the problem, launching a new research initiative called Project Lighthouse in partnership with Color of Change and a nonprofit called Upturn that will study the impact that people’s perceived race has on their Airbnb experience.

The Airbnb partnership is the first time Color of Change has ever come full circle on one of its targets, evolving from critic to collaborator. But, Robinson isn’t ready to stop fighting.

“I feel like Airbnb still has problems,” he said. “They use risk assessment tools that make it so they’re still blocking people out of public accommodations. They’ve had a real impact on cities.”

Richardson, for her part, said one of the things she appreciates most about working with Color of Change is “their absolute candor.”

Waiting for Zuckerberg

Mark Zuckerberg did not attend Color of Change’s first meeting with Facebook. Or the second.

Zuckerberg and Robinson didn’t meet face-to-face until years after Color of Change began its campaign against Facebook, first for allowing Black activists to be doxxed, later for Facebook’s work with police departments, and more recently for its spotty enforcement of policies around hate speech and violent threats.

Their first meeting wasn’t altogether intentional, either. In mid-November 2018, Robinson started getting calls asking him for comment on an exposé The New York Times had just published. It said that Facebook had hired an opposition research firm called Definers to dig up information on Facebook’s critics and their financial ties to Democratic billionaire (and Republican boogeyman) George Soros. Color of Change was one group of critics the Times mentioned by name. The story became an overnight scandal for Facebook, and particularly Sheryl Sandberg, who the story cast as covering up for Facebook’s sins after the 2016 election.

But the incident raised Color of Change’s profile: If Facebook was investigating them, surely they were doing something right? In a Facebook post, Robinson accused the company of “employ[ing] hatred and fear for power and profit” and demanded a sit-down meeting with Sandberg and Zuckerberg. Shortly after, Robinson, Hatch and Collins-Dexter were on their way to Menlo Park to meet with Sandberg.

To Aaron of Free Press, this deft strategic move is emblematic of the way Color of Change works. “Their ability to respond in a way that not only said we expect an apology and accountability, but to also use that to leverage direct lines of communication … at a huge company like Facebook is a testimony to their skills,” he said.

Sitting in a glass-walled conference room, Sandberg apologizing profusely for the “hurt” the story had caused, Robinson recalled. When Zuckerberg wandered by, Robinson said Sandberg waved him inside. Robinson remembered standing awkwardly with Zuckerberg for a few minutes, exchanging platitudes about how there was a lot of work to be done, before Zuckerberg slipped away again.

“He never sat down,” Robinson said.

Rashad Robinson says Mark Zuckerberg wasn’t involved with Color of Change’s early conversations with Facebook.Image: George Frey/Bloomberg via Getty ImagesBut Sandberg stayed, and Robinson pushed her to publicly release the initial results of Facebook’s own civil rights audit, which was already underway, before the end of the year. That audit, like Airbnb’s, was also being conducted by Murphy and the law firm Relman Colfax. A Facebook spokesperson said the company had already decided on that timeline, and so, when Robinson made the demand, Sandberg agreed.

Afterward, Color of Change eagerly broke the news in a press release, logging it as a win: “Color Of Change secures key concessions at meeting with Sheryl Sandberg.”

That meeting marked the start of a fraught relationship between Facebook and Color of Change. Over the course of the next nearly two years, Color of Change’s leaders have often thought they were making progress with the company, only to suffer some sort of setback. There was the time Color of Change and Facebook organized a daylong event in Atlanta, attended by Sandberg and more than 100 civil rights groups, only to be blindsided the week of the event by Facebook publicly confirming its policy against fact-checking politicians’ speech.

“It was a slap in the face,” said Collins-Dexter, who had worked closely with the Facebook team to pull off the event. “They’re saying they’re not going to do the work.”

And there was the time, months later, when the auditors, Robinson, Gupta of the Leadership Conference, and Sherrilyn Ifill of the Legal Defense Fund met with Zuckerberg to discuss how Facebook could prevent census disinformation from spreading. The meeting had been productive, but later, when Robinson went to a dinner with civil rights leaders at Zuckerberg’s house, he ended up squabbling with the CEO over why the far-right media outlet Breitbart is considered a trusted news source at Facebook.

“I interrupted him, and he interrupted me,” Robinson said. “It was never loud, but it was like: What are we doing? I felt like we had a good meeting earlier.”

It was a slap in the face.

But Facebook crossed a bright line for Color of Change and the broader civil rights community in late May 2020. Shortly after George Floyd was killed, sparking protests across the country, President Trump wrote a post on Facebook threatening to shoot looters in Minnesota. Facebook, which has policies against threatening and inciting violence, refused to take the post down, arguing that Trump was describing use of force by the state, a category of speech the platform protects. That post came just days after the president used Facebook to cast doubt on the validity of mail-in voting, which Facebook also did nothing about.

The company’s inaction infuriated both Facebook employees, who staged a virtual walkout in response, and civil rights leaders. Color of Change and others had spent years trying to convince Facebook to put policies in place that would prohibit voter suppression and violent rhetoric. Yet, on June 1, as millions of Americans marched in protest of racial injustice, Robinson found himself on a Zoom call listening to Zuckerberg, one of the world’s most powerful white men, explaining to Ifill and Gupta, two of the world’s most accomplished civil rights attorneys, why those rules didn’t apply here.

“We were stunned about the different interpretations about what voter suppression really means and looks like in this era,” Gupta said.

“I walked away thinking: We need to do the boycott,” Robinson said.

‘A for attendance’

The ad boycott wasn’t Color of Change’s idea. The organization Sleeping Giants, whose entire modus operandi involves pressuring advertisers to ditch problematic brands, had reached out about starting an advertiser boycott against Facebook and was seeking buy-in from civil rights groups. Color of Change had been wary about using this tactic against Facebook in the past. “When a platform has 2 billion people, how many people have to boycott to make a difference?” Collins-Dexter said.

But it had already been compiling a list of companies that made statements in support of racial justice following George Floyd’s death and knew it might be possible to leverage those public commitments to its advantage. “There was a center of gravity where we could wield power over corporations,” Collins-Dexter said. “That really hadn’t happened before and probably wouldn’t again.”

So they agreed to join in. So did the NAACP, the Anti-Defamation League, Common Sense, Free Press, the National Hispanic Media Coalition, the League of United Latin American Citizens and Mozilla. As part of the boycott, the groups set forth a list of 10 demands for Facebook, including that it create a permanent civil rights infrastructure, find and remove groups focused on white supremacy and other extremist ideology, and, crucially, eliminate the political fact-checking exemption.

Together, they lured away more than 1,000 of Facebook’s advertisers for the entire month of July, beginning with what Collins-Dexter calls the “granola” companies — The North Face, REI, Patagonia — followed by multinational conglomerates like Coca-Cola and Pfizer.

Sherrilyn Ifill of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Vanita Gupta of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, Rashad Robinson, Sheryl Sandberg, and Laura Murphy at an event in Atlanta.Image: Color of ChangeThe boycott didn’t go unnoticed by Facebook’s leaders, but they were hardly panicked, either. During a July 1 town hall meeting, Zuckerberg reportedly told Facebook employees that the company wasn’t going to capitulate to advertisers because they’d be back “soon enough.” The following week, Zuckerberg, Sandberg and other Facebook executives did try to appease the organizers during a private video chat, but afterward, Robinson would accuse the company of trying to get an “A for attendance.”

He likened Facebook’s response to the government’s response to Katrina in Color of Change’s early days. “No one was nervous about disappointing Black people,” he said, repeating a line he’s used before to describe Color of Change’s beginnings. “When institutions are not nervous about disappointing our community, all sorts of things can happen.”

The day after meeting with the boycott organizers, Facebook released the third and final installment of Murphy’s extensive civil rights audit, a scathing 89-page rebuke that capped off a brutal week of press for the social media giant. Murphy described Facebook’s approach to civil rights as “reactive and piecemeal,” noting that “the frustration directed at Facebook from some quarters is at the highest level seen since the company was founded.”

But Murphy also pointed to some progress Facebook had made during the course of her two-year investigation. It created a civil rights task force, headed up by Sandberg, and committed to hiring a civil rights vice president to oversee its work in this area. It’s working on developing civil rights training for employees, and it expanded its voter suppression policies, banned praise of white nationalism and created a census interference policy, among other things.

There was a center of gravity where we could wield power over corporations.

Just this month, it launched a Voter Information Center, which aims to disseminate accurate information about the election and register 4 million voters. Gupta described this move as a “really significant” outcome of the civil rights community’s collective efforts.

Facebook also committed to conducting two additional audits with third-party investigators. The first, a “brand safety” audit, will study how effectively Facebook applies its content standards when it comes to paid ads, something the boycott organizers had been asking for. The second audit, set to kick off in 2021, will study whether Facebook is using the right metrics to determine whether it’s enforcing its content policies properly. It’s a study, in effect, of a study.

No end in sight

It’s hard to know which of these changes Color of Change can take direct credit for. It’s harder still to know what impact the boycott had on these changes. Robinson, for one, said he believes the boycott acted as an “accelerator” to decisions that had been bottlenecked at Facebook for too long.

Facebook declined to make any executive available for this story, but spokesperson Ruchika Budhraja said in a statement, “Color of Change is one of the many organizations whose expertise has influenced our thinking over the years. While we don’t always agree, we do encourage input from across the civil rights community as it brings important perspective to our policy and product work at Facebook.”

Murphy, who interviewed more than 100 civil rights and social justice organizations as part of the Facebook audit, said there were many pressure points on Facebook along the way and cautioned against attributing any single change to any single organization.

“Color of Change is only one piece — albeit an important one — of the spectrum of civil rights groups that have been pushing tech companies for several years to pay attention to discrimination and diversity and inclusion issues,” she said. “I think an honest historian would look back on this phase of social media advocacy and say that the civil rights audit, the profound reaction to the killing of George Floyd, the reaction of Facebook employees, and the boycott represent a confluence of factors that helped to propel and advance civil rights changes at Facebook.”

Of course, an honest historian would also have to admit that in many ways, Facebook remains unchanged. It has gotten better at detecting and removing hate speech on the platform, but it’s nowhere near banishing it for good. The boycott and ensuing public scrutiny barely registered as a dip in Facebook’s inexorably rising stock price. Facebook still won’t fact check or remove politicians’ posts when they lie (except in some very narrow circumstances). And, according to one estimate, 76% of the advertisers who took a stand against Facebook were right back on the platform once August rolled around, just as Zuckerberg reportedly predicted.

One organization that never stopped advertising on Facebook: Color of Change. Robinson is unrepentant about that, noting that the boycott specifically targeted for-profit companies, not nonprofits and social justice organizations. “We are getting day in and day out beat on racial justice issues and the ability to live and be heard in our democracy because of how Facebook is set up,” he said. “We can’t leave the platform.”

The truth is, Color of Change wouldn’t be where it is today without the very tech companies it’s fighting to fix. Color of Change’s leaders are not policy wonks. They’re not social workers or former government officials or lawyers (not practicing ones, anyway). But they are the ones who can convince an online army of millions to sign a petition or get Prince Harry to appear in a YouTube video about online hate. They’re digital campaigners — masters of media who know how to rally a crowd. And right now that crowd is on Facebook. And Twitter. And YouTube, and so many of the other tech platforms that have known what it’s like to be on the wrong side of a Color of Change campaign and surely will again.

Prince Harry in a Color of Change YouTube video about online hate.Image: YouTube, Color of Change and ProtocolColor of Change doesn’t just want these online communities to be better for Black and brown people. It needs them to be, because, like it or not, social media is the most powerful tool in Color of Change’s toolbox. It is the medium by which the organization can effect the change its name promises.

One Wednesday at the end of July, Collins-Dexter was back in her attic, once again glued to her computer screen, watching another virtual hearing in Congress. This time, though, it was the CEOs of Facebook, Google, Apple and Amazon feeling the heat, as they tried to convince the committee that their tremendous power is not the problem Collins-Dexter and so many others have warned them about. It felt good to see them squirm. “Sadly it was one of the highlights of my year,” Collins-Dexter said.

A few days later, Collins-Dexter announced on Twitter that she was leaving her full-time role at Color of Change. When people asked, she told them it was because she’s writing a book, which is true, but in reality, she said, she’d been planning on stepping back for a while. For as inspiring as this work is at times, it can be demoralizing, too. “I don’t want to spend my next decade hunting for the humanity in tech and in people who don’t see the full humanity in me and my community,” Collins-Dexter said.

Going forward, she’ll continue to work with Color of Change as a senior fellow, but she wanted to step aside to make room for someone who has the energy to take on the next leg of a journey that has no clear end point in sight. In her sign-off on Twitter, Collins-Dexter promised that the organization was in good hands. Maybe a little too good. “I almost feel sorry for corporations,” she wrote. “Almost.”